After the October feast of Halloween-inspired offerings, in November the local classic film screenings are a bit less abundant, but many are tantalizing nonetheless. Here is my monthly run-down. For those living in the area, or visiting, please support the local cinemas that provide us a unique experience seeing these older films in the way their original audiences did.

After the October feast of Halloween-inspired offerings, in November the local classic film screenings are a bit less abundant, but many are tantalizing nonetheless. Here is my monthly run-down. For those living in the area, or visiting, please support the local cinemas that provide us a unique experience seeing these older films in the way their original audiences did. Before that, a quick shout-out to the Coolidge Corner Theatre, who brought back the Berklee Silent Film Orchestra for an encore performance of their new score to the famous 1925 silent film Phantom of the Opera, along with the screening, on Oct 27th. I so enjoyed this!

Somerville Theatre

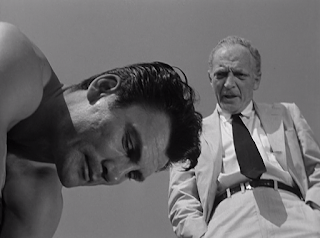

Weds. Nov 2, 7:30 PM: In a reminder that William Shatner had a movie career before Star Trek, the Somerville presents The Intruder (1962), from Roger Corman Productions. I've not seen this one, but the theme is timely as it addresses racism in America, an issue that does not seem to be able to be effectively resolved, nor will it anytime soon. This film addresses the issue of school integration in a Southern town, which was a hot topic at the time. Shatner plays a visitor to the community with an agenda to block integration. Bosley Crowther in the New York Times gave it a mediocre review, saying that it's "crudely fashioned from cliches and stereotypes." But he goes on to say "it does break fertile ground in the area of integration that has not been opened on the screen." Modern audiences must appreciate it more, as it currently sports a 7.8 rating on IMDb. It was directed by Roger Corman from a script based on the novel from Charles Beaumont.

Weds. Nov 2, 7:30 PM: In a reminder that William Shatner had a movie career before Star Trek, the Somerville presents The Intruder (1962), from Roger Corman Productions. I've not seen this one, but the theme is timely as it addresses racism in America, an issue that does not seem to be able to be effectively resolved, nor will it anytime soon. This film addresses the issue of school integration in a Southern town, which was a hot topic at the time. Shatner plays a visitor to the community with an agenda to block integration. Bosley Crowther in the New York Times gave it a mediocre review, saying that it's "crudely fashioned from cliches and stereotypes." But he goes on to say "it does break fertile ground in the area of integration that has not been opened on the screen." Modern audiences must appreciate it more, as it currently sports a 7.8 rating on IMDb. It was directed by Roger Corman from a script based on the novel from Charles Beaumont.  |

| Herbert Marshall, Teresa Wright, and Bette Davis in The Little Foxes |

Fri Nov 11, 7:30 PM and 9:45 PM: A fun dose of 1950s teenage culture is presented in the double-feature screenings of Nicholas Ray's Rebel Without A Cause (1955), and Richard Thorpe's Jailhouse Rock, (1957). Both feature huge stars of the time, James Dean, and Elvis Presley, who both came to sad, untimely ends. But here they are in their prime, which is how, in my opinion, they should be remembered. Both portray anxious, rebellious young men. In the former, Dean plays a high school student who rebels mainly against his family and society, and in the latter Elvis is burgeoning musician who gets into trouble with the law, but then gets his big chance. It's been years since I've seen 'Rebel' and with my appreciation of classic film, and the strong reputation today of Nicholas Ray, I may try to make it back to the Somerville for this one. Jailhouse Rock is new to me, and I love me some 50s rockabilly, so if I can stay awake I would definitely stick around. This one is known for the big set-piece around the Jailhouse Rock song. Another sad side note, Elvis's leading lady in this film Judy Tyler was killed in a car wreck at age 24 just a few days after filming wrapped. Apparently as a result Elvis refused to watch the complete film.

Check out the official trailer here:

Brattle Theatre

The Brattle has two series planned with intriguing names: "Bad Hombres and Nasty Women" (will Donald Trump show up??) and a celebration of Shakespeare called "The Bard Unbound -- Shakespeare on screen". Fans of films from the classic era would enjoy the following in this series:

Thurs. Nov 3, 7:30 PM A Fistful of Dollars (1964). Clint Eastwood got his start in this, the first in the 'spaghetti Western' trilogy by Italian director Sergio Leone, perhaps best known for The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly. Leone was known for quick cutting between medium shots and extreme close-ups, and his bringing brutal violence to the western genre. This film was on my list to watch during my "Western movie summer," but unfortunately I didn't get to it. I won't see this screening, but would recommend it to fans of Eastwood and Westerns. IMDb summarizes the plot as "A wandering gunfighter plays two rival families against each other in a town torn apart by greed, pride, and revenge." It's being screened in 35 mm, and showing in a double feature with the 1997 film Perdita Durango, starring Javier Bardem.

Thurs. Nov 3, 7:30 PM A Fistful of Dollars (1964). Clint Eastwood got his start in this, the first in the 'spaghetti Western' trilogy by Italian director Sergio Leone, perhaps best known for The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly. Leone was known for quick cutting between medium shots and extreme close-ups, and his bringing brutal violence to the western genre. This film was on my list to watch during my "Western movie summer," but unfortunately I didn't get to it. I won't see this screening, but would recommend it to fans of Eastwood and Westerns. IMDb summarizes the plot as "A wandering gunfighter plays two rival families against each other in a town torn apart by greed, pride, and revenge." It's being screened in 35 mm, and showing in a double feature with the 1997 film Perdita Durango, starring Javier Bardem.Sat. Nov 19, 12:30 PM: Henry V (1944). This is the version with illustrious Shakespeare interpreter Laurence Olivier. Filmed in Technicolor and directed by Olivier himself, it is a faithful adaptation of the play. Since at the end of this tale as told by the great master, Henry and England emerge from their war with the French victorious, the film version was partly funded by the British government to fuel positive morale in the public during WWII. Showing here in a digital transfer.

|

| Laurence Olivier as Henry V |

|

| Olivier as Richard III |

Sun Nov 20, 7:00 PM: The new 4k restoration of Orson Welles' adaptation of the Falstaff story Chimes at Midnight, is presented. I had the opportunity to see this a few months ago at the Coolidge, and it's fantastic. I previewed that screening here. It is a bit hard to follow, if you don't speak Shakespearean English fluently, and the sound is famously off in parts, but it has the brilliance of Welles, both acting in a role he considered his favorite, and directing in black and white with his usual expressionistic flourishes. A handsome, roguish Keith Baxter has the lead, and Sir John Gielgud, Jeanne Moreau, Margaret Rutherford all appear in critical roles. It was not a critical success at the time it was released, but it's now considered in the top echelon of the Welles filmography.

|

| Baxter and Welles in Chimes at Midnight |